Optimism vs Optimization

Candide in Silicon Valley

With the triumph of Large Language Models and Deep Neural Networks, we have entrusted our understanding of reality to statistics. Moral considerations have been sidelined in favor of frequencies, residuals and R-squared values. The confusion matrix is now the only type of confusion modern humanity is allowed to experience.

The frantic pace of innovation leaves us little time to ask meaningful questions or to genuinely feel the vertigo of the acceleration we are hurtling into. Angst as defined by Kierkegaard1 has given way to the Fear of Missing Out (FOMO). Though seemingly different, these two anxieties are more similar than they first appear.

Both fears are ultimately incurable - only death can silence them. Until then, we constantly experience something new, endlessly running on treadmills that have been interconnected through gears of different sizes. We keep running, yet we remain stationary. Society runs too, but it also remains stationary, albeit at a different pace. The largest gear in this infernal treadmill is technology. Technology moves swiftly, but in what direction?

Technology optimizes, achieving more with fewer resources. This is indisputable. We have clear reasons to optimize, but do we have reasons to be optimistic too? Consider our most famous optimist, the optimist “par excellence”: Candide from the Voltaire’s novel. If suddenly dropped into our modern world, Candide would be dazzled. He'd gape at smartphones, mistaking them for magical mirrors; he'd marvel at electric cars, AI assistants, and the ability to video chat with someone across the globe. Surely, he would say, this must be the best of all possible worlds. But is it really so? Eager to adapt, Candide would open a TikTok account, where he’d follow dozens of self-help gurus, including a reincarnated Pangloss now rebranded as a life coach with millions of followers and a best-selling book titled Radical Optimism: Why Everything Happens for the Best. Candide, still painfully trusting, would invest all his savings in a cryptocurrency called “PanCoin,” only to see it crash the next week after a rug-pull scandal involving the same guru.

He’d fall in love online with someone claiming to be Cunégonde 2.0—an influencer with filtered selfies and vague poetic captions—but after wiring her money for a "spiritual healing retreat in Bali," she vanishes. When Candide tries to report it, he’s bounced between automated chatbots and customer service lines that never connect.

Jobless, scammed, and emotionally spent, he ends up at a mindfulness commune in Silicon Valley, convinced once again by Pangloss that all of this suffering is, somehow, part of a grand design. Candide still clings to the hope that, with just a little more patience, things will make sense. And maybe they will. But only after he's sold his kidney in a shady "bio-optimization clinic" in exchange for exposure on a podcast. So now he is jobless, scammed, emotionally spent and with only one kidney left.

Voltaire would have laughed - and wept. Should we feel the same? Our modern society, enabled by technology is at war between optimism and optimization. Technology optimizes, but rarely provides ground for genuine optimism.

Optimism implies that things will ultimately improve and turn for the better, it’s a psychological concept, focused on silver linings, and half-full glasses. Optimization instead is a mathematical concept, taken from Applied Mathematics and Operational Research. As Wikipedia2 defines it:

An Optimization problem consists of maximizing and minimizing a real function by systematically choosing input values from within an allowed set and computing the value of the function. The generalization of optimization theory and techniques to other formulations constitutes a large area of applied mathematics.

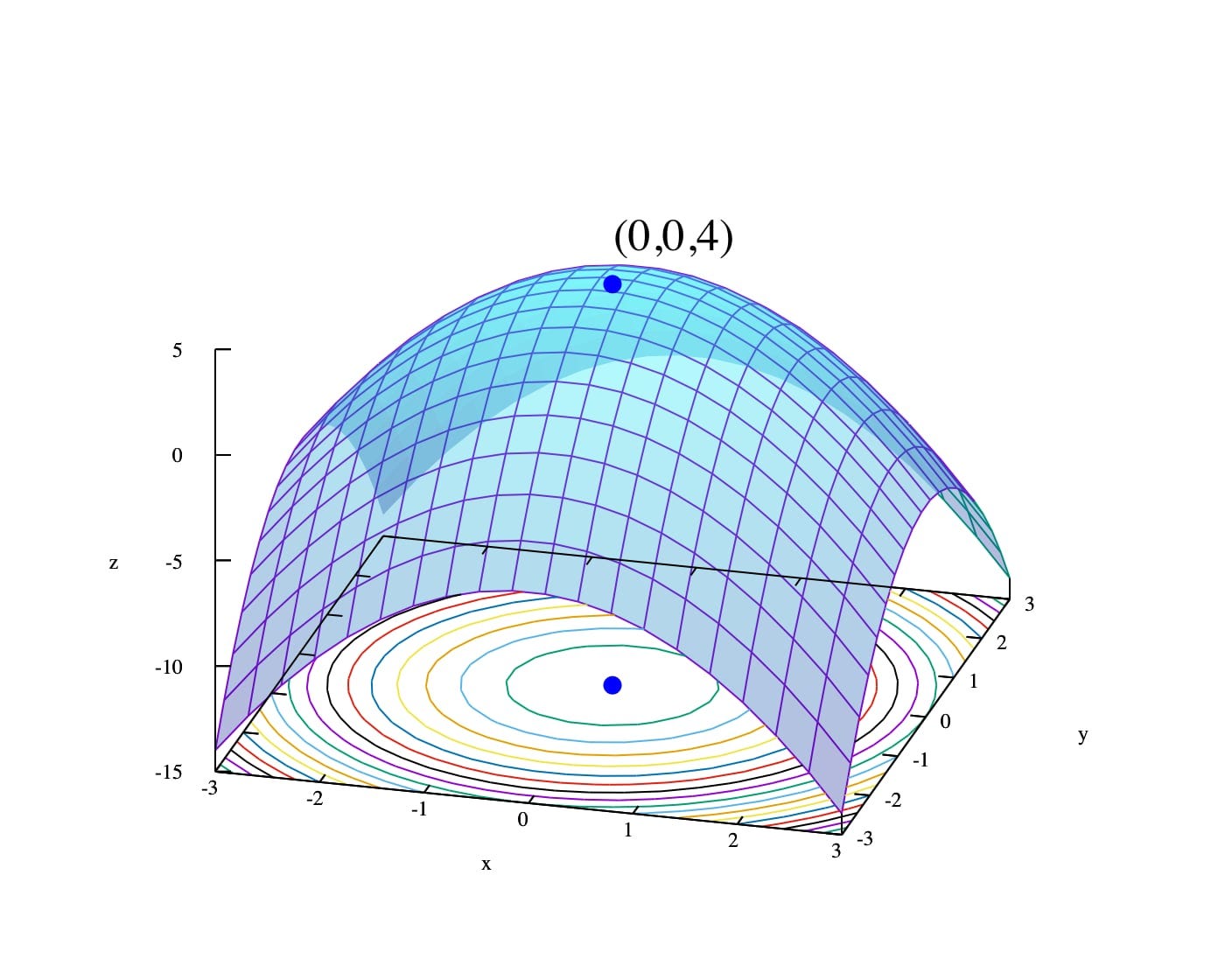

Optimization seeks the maximum or minimum possible values of a certain function. If we are computing our revenues or the value of portfolio, we want to find the points in the curve maximizing the value. Sometimes we want to minimize the value, such as in Machine Learning when we try to minimize the loss function, i.e. the residuals, the errors our model is producing in its predictions. In this case we want our predicted values to stick as close as possible to the real distribution, so the difference between them and the predicted values should be close to zero.

Optimization is one of the most important field of research, with many techniques and tools. One common problem, which I find very interesting from the philosophical point of view, is the local minimum/maximum problem, also known as the “Explore vs exploit” dilemma. We start optimizing what we see, but we don’t know if we are stuck in a local minimum/maximum. There is a cost though for exploring the data around us, we cannot do it forever without making the optimization slow or inconvenient. We have to find a compromise between our exploration phase, where we look around, and exploitation, where we work in a specific direction to minimize/maximize our function.

This resonates a lot with “the best of possible worlds” from Leibniz’s Theodicy3, which firstly originated the grim satire of Voltaire’s Candide. Why – of all possible worlds – did God create exactly this one? How we justify the existence of our own world? This world seems far from perfection, but – Leibniz argues – it contains just the right amount of evil in it, the right amount necessary to justify it. This sounds a lot like an optimization problem, considering the best world amidst all possible worlds while finding a local and a global optimum.

This is the very essence of optimism, thinking what happens to you is the best possible outcome that could have ever happened. Optimization instead is an empirical problem: it looks for minimization and maximization inside specific boundaries. It does not look at all the “possible” outcomes, it is strictly set inside the boundaries where the conditions apply.

Economics and Technology strive for optimization, and define optimal outcomes. We want to have more goods, to increase profits, to have mobile connections with higher bandwidth, to have larger, cheaper, and more efficient batteries. Pretty much everything technology and economics are doing is an optimization problem, driven by efficiency and cost reduction.

This optimization problem does not bring us magically to a better society. Optimization and optimism are very different, and not just for moral reasons. You don’t need a Theodicy for that, Game Theory is more than enough, such as for example the Tragedy of the Commons4 illustrating a fundamental tension between individual rationality and collective well-being. In this classic dilemma, multiple agents share access to a finite, exhaustible resource—such as a fishery, pasture, or atmosphere. Each individual is incentivized to maximize personal gain by exploiting the resource, even though such behavior, when mirrored by others, leads to the degradation or collapse of the shared asset. The result is a paradox: rational decisions at the individual level produce irrational outcomes for the group. This model highlights the critical need for cooperation, regulation, or incentive redesign to avoid long-term collective loss. When we bound rationality to a single agent, and each agent optimizes for itself, the collective outcome could be way far from optimal. We see this in many problem, from ecological problems to political problems, with issues such as free speech and the diffusion of weapons.

Big tech entrepreneurs often excel in optimizing personal outcomes but falter in complex political scenarios, unable to grasp intricate social dynamics fully. Their optimized solutions rarely predict emergent, nonlinear phenomena or unforeseen developments, or even “black swan” events. It’s not just about optimism: optimization does not get well along with pessimism either. Pessimism is just an inverted optimism, but optimization per se does not distinguish between minimization and maximization, they are both optimization problems. The optimizer does not see the glass as half empty or half full, only if it is optimally empty or optimally full.

The problem of the big entrepreneurs is that they incorrectly project an optimization problem over an optimal society. They see this in positive and negative, and tend to steer society from “existential risks” that exists in very simple – and unrealistic – boundaries. They are often ill-equipped to see the risks of non-linear phenomena, or complex behaviors emerging from the very own world they changed through their relentless optimization efforts. Had computers existed in 1880, they might have predicted unsustainable horse manure growth due to the explosion in human population, so they would have worked to reduce the amount of manure pro-horse, but would have failed entirely to anticipate cars, because they were outside of the boundaries of their optimization problem.

The best approach here is the philosophical discipline of skepticism. Skepticism is the attitude of doubting or questioning the validity of certain knowledge, beliefs, or claims. As a method of inquiry, skepticism allows us to transcend boundaries, radically question assumptions, and approach everything with greater caution. Skepticism does not reject optimizations; it simply examines their purpose and underlying beliefs about delivering value to society from a different perspective.

Skepticism, particularly technoskepticism, is not a cure for the malaises of contemporary society but rather an antidote to the venom of unduly zealous techno-optimizers who, in their obsessions, risk dooming the world. Optimism and optimization should remain distinct—not only morally but also pragmatically. Making things better does not necessarily mean making them "the best." Understanding this distinction could prevent us from blindly pursuing “optimal” outcomes at the expense of society, as many leaders of Silicon Valley are currently trying to do.

Kierkegaard, Søren. The Concept of Anxiety: A Simple Psychologically Orienting Deliberation on the Dogmatic Issue of Hereditary Sin. Translated by Reidar Thomte and Albert B. Anderson, Princeton University Press, 1980

Leibniz, G.W. Theodicy, Essays on the Goodness of God the Freedom of Man and the Origin of Evil, Open Court, 1985, online https://homepages.uc.edu/~martinj/Philosophy%20and%20Religion/Problem_of_Evil,_Free_Will_and_Determinism/Leibniz%20-%20Theodicy.pdf

Hardin, Garrett (1968). The Tragedy of the Commons. Science, 162(3859), 1243–1248, online at https://math.uchicago.edu/~shmuel/Modeling/Hardin,%20Tragedy%20of%20the%20Commons.pdf

Thanks Francesco for the valuable contribute. I was thinking something similar, I'll try to put it in words in a few days, hopefully. As a philosopher, I never liked skepticism too much. Following a path close to yours, I will probably end in a epistemological openness: Economics thinking should not be the only game in town.